ANSWER:

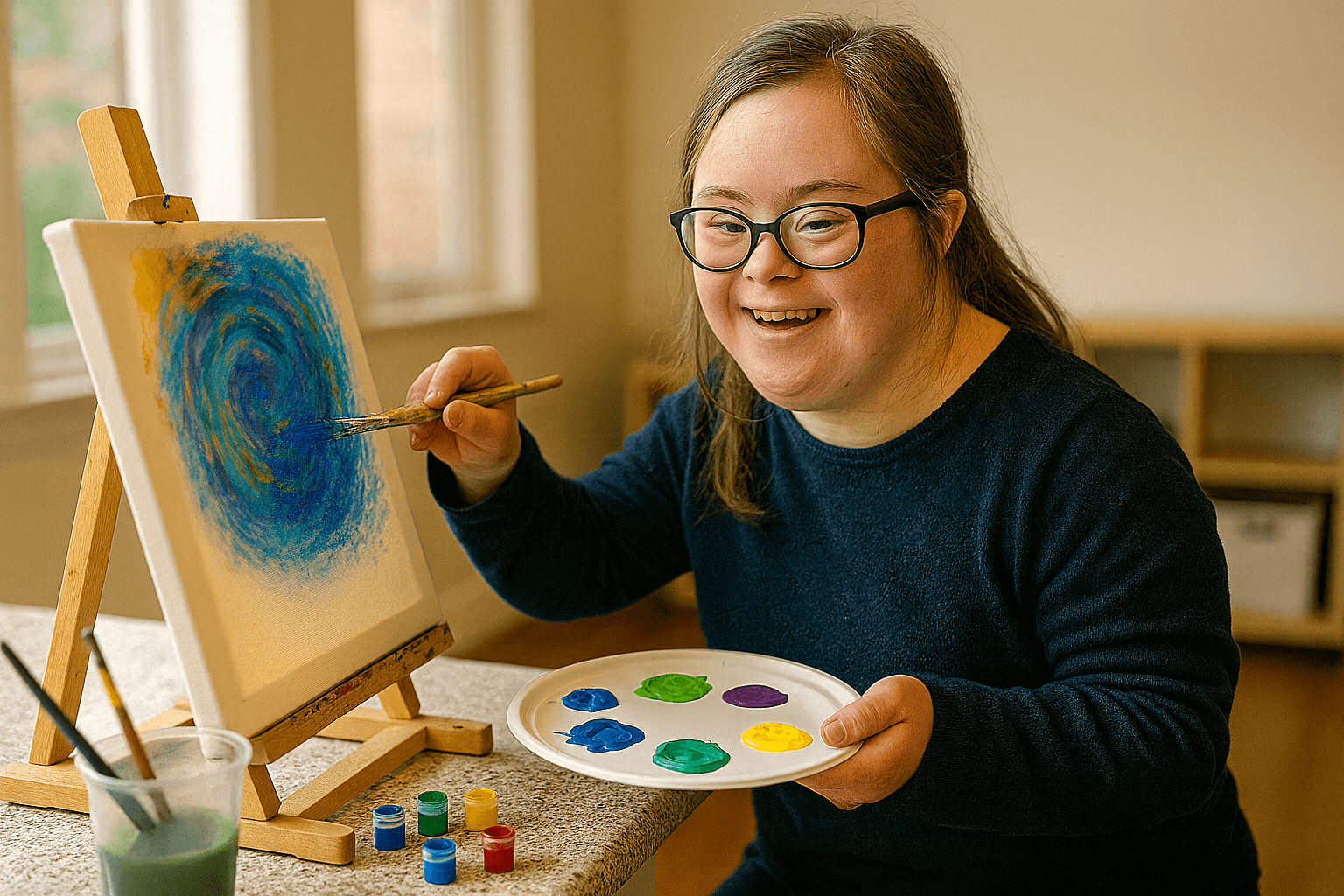

First, let’s look at what happens during adolescence in general. This stage brings major hormonal shifts that affect every teen. There isn’t a clear connection between developmental delays and how — or when — those changes unfold.

The strength of these changes varies from child to child, depending mostly on their individual hormones. Still, a child’s diagnosis and level of functioning shape how these shifts are expressed, especially in communication and relationships.

So, what, exactly, is adolescence?

Caring for a child with special needs affects everyone.

Our Siblings Are Special Too guide shares ten grounded, actionable ways to support siblings with sensitivity.

The Nature of Adolescence

Adolescence is the transition from childhood to adulthood, marked by physical, emotional, and cognitive changes.

The most phenomenal description I’ve found in the literature is from Judith Mishne’s book Clinical Work with Adolescents. She describes how adolescents may swing between extremes in a way that “would be deemed highly abnormal at any other time of life.” For example:

“to fight his impulses and to accept them; to ward them off successfully and to be overrun by them; to love his parents and to hate them; to revolt against them and to be dependent on them; to be deeply ashamed to acknowledge his mother before others and, unexpectedly, to desire heart-to-heart talks with her; to be more idealistic, artistic and generous, and unselfish than he will ever be again, but also the opposite: self-centered, egotistic, calculating.”

Understanding this normal turbulence is the first step in learning how to parent any teen – including one with special needs.

The Brain Under Construction

Why is adolescence so full of intense emotions, mood swings, and impulsivity?

I describe this stage of development as the “hard hat area.” Picture a construction site.

Before construction begins, the area is calm and quiet. Then demolition crews dismantle and remove all familiar structures – causing chaos. A passerby might even assume the construction to be destructive.

Months later, it becomes clear that the destruction and havoc were essential to the creation of a larger, more sophisticated building.

That construction project is your child’s brain.

Prior to adolescence, children seem to have absorbed the principles they were taught, and their behavior is predictable and familiar.

At the onset of adolescence, all this begins to change. Hormonal changes trigger the brain’s “demolition and reconstruction” process, dismantling old pathways to make room for new ones.

It can be painful for parents to feel that the “building” they invested in — instilling their child with values and skills — has been torn down. Remember, what you’re seeing now is simply the behavioral manifestation of neurological reconstruction, and when it’s complete, a polished and refined version of your child will emerge.

The Changes of Adolescence

In adolescents with developmental delays or disabilities, hormonal changes are often similar to those in typical teens, so they experience many of the same shifts.

1. Neurological Changes: As the brain develops, adolescents often experience irregular sleep patterns, closely tied to rapid physical growth. Growth hormone is released during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, so the adolescent brain signals tiredness more often to trigger frequent REM cycles – giving the body a chance to maximize growth.

Your teen’s increased need for sleep is a natural part of healthy development, not laziness.

It is crucial to monitor your teenager’s physical health and development while these changes are taking place. Regular checkups at the pediatrician should include a full physical exam, blood work, blood pressure, height, weight, and screening for eating disorders and curvature of the spine.

2. Emotional Changes: In adults, the logical center – the prefrontal cortex – will override the impulsive directives given by the emotional center – the amygdala.

In adolescents, the logic-driven prefrontal cortex is undeveloped, leaving the amygdala to respond to events and the environment using emotion and instinct, lacking logic and foresight. You’ll notice that your adolescent is more sensitive, emotionally volatile, and impulsive because they lack the prefrontal cortex’s logical interventions.

Additionally, the amygdala’s job is to prepare the body to react to stress, so adolescents are easily overwhelmed because the amygdala is still underdeveloped.

3. Hormonal Changes: Adolescence brings a surge of hormones released at much higher levels than before. This flood of new hormones — mixing with the ones already there — explains why your teen may be moody, irritable, or extra sensitive at times. Both typically developing teens and those with disabilities may cry more often, struggle to regulate their emotions, and find it difficult to express what they feel.

4. Relational Changes: One of the most central aspects of childhood is dependence on parents. As they begin to move toward the independence of adulthood, adolescents instinctively turn away – often sharply and painfully – from their parents. Even if a teen with special needs may not ultimately reach the same level of independence as their peers, they still experience this developmental push. They may express it with words like, “Leave me alone,” “I don’t need you anymore,” or “Don’t tell me what to do.” For parents, those words can sting, but they’re a sign of something healthy and universal: the child’s growing need to move from dependence toward autonomy.

5. Social and Emotional Separation Of Genders. During adolescence, the structural differences between male and female brains experience a growth surge. This leads to noticeable social and emotional differences between boys and girls of the same age.

During the earliest stage of adolescence, girls mature faster than boys in cognitive areas. They may become highly verbal during negative moments and speak in an escalated tone of voice. Your daughter with special needs may also become very conscious of her appearance.

Boys, on the other hand, continue to develop motor skills, and may express themselves physically, especially during episodes of sibling rivalry.

Recognizing these gender-based patterns can help you respond with empathy and offer the guidance each one needs.

Tools for Teens

As tough as the teenage years can get, don’t despair. Continue to use the strategies we’ve discussed previously, such as the INB (Ignore Negative Behaviors) strategy discussed in part 4. When a behavior can’t be ignored, use SWC (Separate Without Comment) – only until your child is too big or strong for physical intervention to be safe.

Using Missions to Transmit Values

Another strategy from the Hands Full Parenting approach that’s incredibly helpful during the teenage years is State Your Mission. Missions are a practical way to convey your values to a teenager who’s navigating the tension between his desire to separate and become independent of you and his need (albeit reluctant) to learn from you.

Because missions avoid using direct commands, teens can absorb the value being conveyed with less resistance. Missions reframe a command (“Pick up the towel”) into a situational fact (“Towels belong on the rack”).

Ideally, missions

- Contain no more than ten words

- Don’t include the words “you” or “your”

- Are stated calmly

- Do not come with an expectation of immediate compliance

After stating the mission, if your teen completes the task, thank him pleasantly. If not, you may repeat the mission calmly after 15 minutes, using the same language you used previously. You can also complete the task at any time on your own – ideally, not in front of your teen.

Always keep the goal in mind: not to get the task done, but to build your child into a responsible adult who has integrity and strong values, and will do the right thing without your help.

This Too Shall Pass

Finally, remember the teenage stage is just that – a phase.

No matter how intense these changes feel in the moment, they’re part of a specific developmental stage. And in time, they will pass.

OPWDD Guidance

OPWDD Guidance Residential

Residential Family Support

Family Support Services for Children

Services for Children Services for Adults

Services for Adults Services for Children 0-3

Services for Children 0-3 Adult Acute Care

Adult Acute Care

.avif)

.avif)